Air Canada : Visiting Cognac (At an Escargot’s Pace)

AIR CANADA Visiting Cognac (At an Escargot’s Pace)

Our writer takes the slow road to meet brandy distillers – with a Stop for snails à La charentaise along the way.

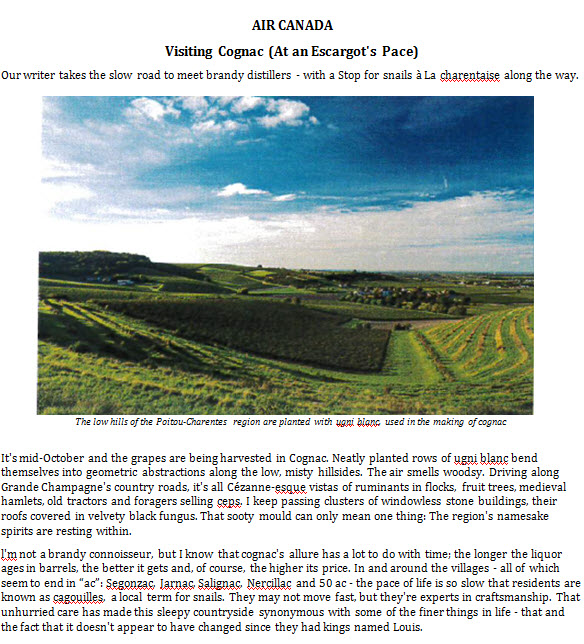

It’s mid-October and the grapes are being harvested in Cognac. Neatly planted rows of ugni blanc bend themselves into geometric abstractions along the low, misty hillsides. The air smells woodsy. Driving along Grande Champagne’s country roads, it’s all Cézanne-esque vistas of ruminants in flocks, fruit trees, medieval hamlets, old tractors and foragers selling ceps. I keep passing clusters of windowless stone buildings, their roofs covered in velvety black fungus. That sooty mould can only mean one thing: The region’s namesake spirits are resting within.

l’m not a brandy connoisseur, but I know that cognac’s allure has a lot to do with time; the longer the liquor ages in barrels, the better it gets and, of course, the higher its price. In and around the villages – all of which seem to end in “ac”: Segonzac, Jarnac, Salignac, Nercillac and 50 ac – the pace of life is so slow that residents are known as cagouilles, a local term for snails. They may not move fast, but they’re experts in craftsmanship. That unhurried care has made this sleepy countryside synonymous with some of the finer things in life – that and the fact that it doesn’t appear to have changed since they had kings named Louis.

Arriving at the town of Cognac’s main square, l’m feeling almost unsure what era l’m in. These cobblestone streets must have looked much the same in the 17th century, with the exception of a few signs here and there. The sensation is reinforced when I come across a crumbling old building whose sagging wood beams and disintegrating gargoyles have stood here for some 400 years. Behind the open door, an old-fashioned bookbinder is toiling away in the sunlight. With all the iron tools, forges and binding implements, it looks like a blacksmith’s denfrom the middle Ages. Jérôme Betin is Lanky, genial and clearly not in any rush whatsoever. There’s also something slightly loopy about him, in a Mad Hatter sort of way. He isn’t actually selling any books; the way his business works, he explains, is that his customers bring him hardcovers that they want specially bound, old editions that are falling apart or rare books that need extra care. He shows me some magnificent examples, embossed with gold lettering and intricate latticework. It makes me wish l’d brought along my beat-up copy of Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel, especially since Monsieur Betin has a peculiar tendency of punctuating his sentences with wild giggles.

I step even further into the Dark Ages later that day when I open the heavy wooden door to the Michel Forgeron family cellars. Their walls are black with that same mould; as I enter, a piece flakes off the ceiling and wafts slowly to the floor. “It’s called la torule,” explains the blue-overalled patriarch, Michel Forgeron. His wife, Francine, her hands gnarled from years of trimming vines with shears, is operating the pressoir as their son Christophe brings in grapes that his brother, Pierre, just harvested in the fields. The family makes artisanal cognac the old-fashioned way, from growing the grapes to distilling. “La torule is a fungus,” Michel continues, “and a by-product of the angels’ share.” La part des anges, he tells me, is the liquid that evaporates when cognac ages in barrels; about two percent is lost each year. One reason why aged cognac is so expensive is that so much vanishes into the ether. As the fumes rise, they nourish these colonies of black mould, which seem to be watching us as we watch them.

“Making cognac requires so much patience,” Christophe says, walking me through the premises. “Some say it’s about controlling time, but it’s also a celebration of time.” He climbs a Ladder up to the top of an immense foudre full of cognac and hands me a glass. The young eau-de-vie smells overwhelmingly alcoholic, with a tongue-numbing attack. Then, leading me deeper into the chai, he dips a glass wine thief into an old, dust-coated barrel and offers me a taste of 30-year-old cognac. It still has a hint of the burn that Locals call l’agressif, but that quickly dissipates as a kaleidoscope of flavours plays over my tongue. I taste dates braised in molten caramel with roasted hazelnuts mixed in, followed by hints of jasmine and beeswax, all rolling out on a dark chocolate finish.

Out in the vineyards, the scene couldn’t be more campagnard: Michel is standing under a walnut tree as old accordion songs crackle from his tractor’s radio. Cracking a walnut, so fresh it’s still milky white and soft, he tells me that the main reason for Cognac’s success is the Charente river. It began as a commercial centre for products such as salt brought in from the nearby Île de Ré (still a source for premium fleur de sel), paper (Rizla rollies, notably, were invented near here) and wines and cognacs were sent to the sea for export from here. “Everybody in Cognac is an artisan,” Michel comments, noting that even the big houses like Rémy Martin work with small-scale growers.

l’m finding that the whole region of Poitou-Charentes, which Cognac belongs to, is a hotbed of artisanal production. It’s renowned for its raw-milk dairies, and the only thing better than the many goat cheeses is the fresh-churned butter, often spiked with crystals of salt. You can buy brook-fresh red-spotted trout from a pisciculteur in a former flour mill where schools of muscular fish dart along the riverbed. At the marketplace in the centre of town, surrounded by locally grown produce, I strike up a chat with a snail vendor who is out of fresh snails. Héliciculteurs also sell baskets of fresh snails from the trunks of their cars in a nearby village on Saturday mornings, he tells me. Seeing my “oh well, forget about that” look, he mentions that he’ll be preparing snails that evening at a communal-dining place in Luchac called Chez Bruno. We shake hands and agree to meet there at dinnertime.

When I get to that “ac” a few hours later, dusk is settling over the valley. The kinky-haired snail man, Christian Navarro, greets me at the door with a broad grin. He’s had a few and is in high spirits. He pours us each a glass of pineau des Charentes (another local specialty, made by mixing wine and grape pressings with young cognac) and then takes me into the kitchen, where he points proudly at a massive pot full of bubbling snails. It turns out to be escargots à la charentaise, one of the region’s traditional recipes of snails cooked with pork belly, country ham, garlic, white wine and parsley. He ladles out a portion and tears me a hunk of baguette. It’s not for the faint of palate; imagine the most extreme, virile plate of mussels ever. But the way the calamari-esque escargots meld into the porky, garlicky persillade is every bit as mind-blowing as the 30-year-old cognac I tried at Forgeron. Watching the long tables fill with laughing, feasting villagers, it occurs to me that they’Ve been having these sorts of get-togethers here for centuries. Cagouilles eating cagouilles.

But the ultimate in time travel is my visit to the Seguin Moreau cooperage. The company manufactures and supplies wine barrels to most of the great producers in France, and it still makes the casks mainly by hand, the way it did in the days of Asterix and Obelix. Burly men wield mallets over their heads and knock iron rings onto bowed ribs of oak. Others toast the assembled barrels over open fires. One of the secrets to the quality of the barrels is that tiny microscopic fungi form on the wood as it is drying – aromatic precursors that express themselves when the wine contacts the wood, adding other dimensions of flavour.

Next door are long greystone buildings with black angel-share roofs, the main storage facilities belonging to Rémy Martin. Inside these aging caves, it’s so eerily hushed and sombre that I find myself whispering. A sign warns against taking photographs as these warehouses are ATEX areas. The air is so full of flammable vapours that a flashbulb can trigger an explosive reaction, the guide explains. One time a warehouse caught on fire, and the Charente river burned for three days; there was that much alcohol in the water. In one basement is an earthen room full of dust clumps, cobwebs and ancient barrels called tierçons. These contain the finest old stocks of Rémy Martin; the current release of Louis XIII Rare Cask, for instance, retails for $25,000 per bottle. The barrels are monitored by the master blender and maître de chai Pierrette Trichet, whose role our guide compares to that of a high priestess. It’s a relief to find that she couldn’t be more down to earth. A stocky woman in her fifties, with a boyish over-the-ears haircut, she’s been working here since she was 23 years old and now has one of the most highly developed senses of smell on earth. When I ask her how best to taste cognac, she smiles: “To taste is to share, so just Like this.” As we sit together in one of Rémy’s countless castle-like facilities, she shuts her eyes and sniffs gently before taking a sip. “Cognac opens up with the heat of the mouth,” she exclaims. As she comments on notes of figs and Licorice, throwing in words like “miracle,” it’s clear how much she enjoys her work.

Where big producers like Rémy Martin emphasize consistency – one of the main roles of the blender is to ensure that the various cuvées taste the same year in and year out – the Grosperrin company seeks out variability and the individuality of particular plots and times. My last stop is to meet Guilhem Grosperrin at a tasting laboratory in Saintes, where his firm La Gabare specializes in minuscule batches of vintage cognac sourced from unique collections. “Many people hold on to old stocks of cognac here,” he says. “Cognac improves and concentrates as it ages in barrels and is, therefore, both an investment and a portrait of a moment in time. l’m interested in the stories these old cognacs tell, so my job is to find the people who own ancestral barrels and convince them to allow me to bottle very limited runs of their cognac millésimé.”

Over the next couple of hours, we taste through his barrels and old bottles, sampling rarities he’d picked up from a magistrate’s widow in Paris or from a family that had been exiled during World War II but had managed to hide their barrels, even a 200-year-old cognac (in bottles since 1919) that tastes herbal, perfumed, medicinal and altogether unlike anything l’ve ever encountered. “Think back to how people lived in 1810. This is a witness of that era,” Grosperrin notes. ‘It’s no longer cognac. It’s history.” As we taste, I suddenly understand: Cognac is a time machine, and it has taken me for a wonderfully slow ride.